LONDON, United Kingdom — Two decades ago, supermodels such as Naomi Campbell, Cindy Crawford, Christy Turlington and Claudia Schiffer claimed they’d rather go naked than wear fur, which they saw as synonymous with animal cruelty. By contrast, today’s most famous Insta-models, from Kendall Jenner and Bella Hadid to Cara Delevigne and Adwoa Aboah, have all walked in haute fourrure shows, veritable spectacles of fur-mania.

And yet, earlier this month Gucci announced it would go fur-free. “It’s not modern… It’s a little bit out-dated,” Marco Bizzarri, chief executive of the Italian brand, told BoF at the time. “It’s not about the Millennials or the new generation,” Bizzarri insisted. But the ban could pay dividends with Gucci’s young client base. Millennials, whom Deloitte describes as more ethically minded than previous generations, presently account for more than half of Gucci’s shoppers, up from 40 percent two years ago, according to analysts at Mainfirst Bank.

Millennials consistently identify sustainability as a key factor in purchasing patterns. “I definitely think people are far more aware of what they’re buying, eating and wearing than they were 10 or 15 years ago,” Yvonne Taylor, senior manager of corporate projects at PETA (People for Ethical Treatment of Animals) UK, told BoF last year. “Items that were once a status symbol are fast becoming a badge of shame.” But today’s youth are unburdened by the campaigns of animal rights groups compared to their counterparts two decades ago. They are also notably influenced by celebrities such as Rihanna, Kim Kardashian West and Beyoncé, who all regularly wear fur and circulate imagery of themselves on their Instagram accounts.

“Our future is bright because of Millennials,” argues Charlie Ross, head of international marketing and sustainability at Saga Furs, a fur supplier, which has its sights set on the next generation of consumers. “The fastest growing category in fur is fur trim and across the board, they felt that the consumer is younger and they’ve done their homework on sustainability and they’ve made their decision… It’s people who are buying their first fur piece, which might be a Moncler [jacket]. That will hopefully segue into a fur coat later on.”

In recent years, fur has moved well beyond the mink coat, popping up in more accessibly priced — and socially acceptable — places, from military parkas to pom-poms to shoe linings. Take Fendi’s Bag Bugs, for instance, which drew criticism when they first launched due to their high price tags. However, the furry Muppet-like bag charms created months-long waiting lists. They’re small yet quirky, more “cute” than “deathly” and resoundingly described as “fun”. Meanwhile, the Italian brand’s “Karlito” keychains — made in the image of Karl Lagerfeld, Fendi’s creative director — cost double the price of its Bag Bugs and sold out before they even hit the stores. Elsewhere, Anya Hindmarch and Charlotte Simone have also carved out strong businesses for accessibly-priced fur charms and scarves.

“We definitely feel a renewed interest, and perhaps it’s because [a younger generation’s] style preferences are finally being taking into account,” say Barbara Potts and Cathrine Saks, the design duo behind Saks Potts, the Copenhagen-based label, now in its eighth season, known for its colourful shearling, mink and fox fur outerwear. “Real fur has been in hibernation for a very long time,” the young designers add. “It was, and to a degree still is, characterised as expensive and old fashioned, but nothing could be more wrong. In our experience, both our generation (20-year-olds) and older generations are interested in [fur].”

“These are the daughters of what we like to call ‚the missed generation,’” says Ross of Saga Furs.

“Their mothers — the baby boomers — didn’t buy fur, but their grandmothers did.

Millennials are also turning to faux fur. In the US, for instance, the market has grown 2 percent from 2012 to 2016 and is now worth $114.6 million.

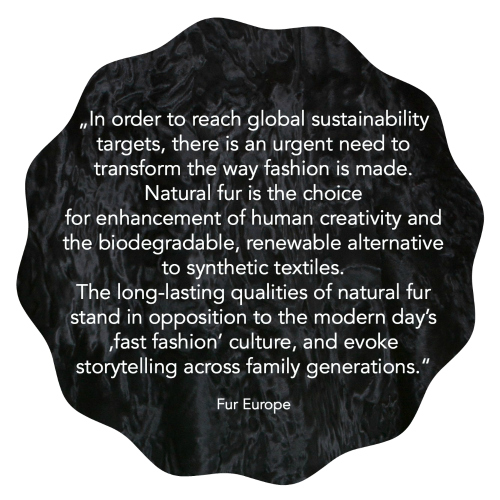

But some fur makers contend that faux-fur is worse for the environment than the real thing.

“Fake fur is the least ecological product, which is done with plastic and non-renewable materials,” says Thomas Salomon, general manager of Yves Salomon, the family business that has been crafting fur since 1920 for houses such as Christian Dior, Yves Saint Laurent and Jean Paul Gaultier. “When you say [fur] isn’t modern, you only have to look at all the girls like Rihanna wearing it today, whether it’s sneakers or a bag, on a hoodie or in a parka.”

Sources Link:

- The Business of Fashion Will Millennials Boost the Fur Trade

- Fur Europe: http://www.fureurope.eu/video/sustainability-of-fur/